Dietmar Schantin, founder of Institute for Media Strategies, speaks on the dangers of fake news, where it came from, and the importance of media regaining public trust.

The Drum recently hosted their Media Slap event—a day on which to hear from successful entrepreneurs in the media world speak on different intriguing topics. Dietmar Schantin, the founder of Institute for Media Strategies, spoke today on a topic that has grown exponentially in a short amount of time: fake news.

Dietmar began with some basic definitions to give us some context. First, what is fake news? The Collins English dictionary defines it as, ‘false, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting’. Another definition was, ‘created to be widely shared online for the purpose of generating ad revenue via web traffic or discrediting a public figure, political movement, company, ect’.

Dietmar emphasizes that this sounds like a new concept, but it is in fact, a very old concept. The first ‘fake news’ story was actually recorded in 1835. John Hershall, a British astronomer based in Africa, described seeing through a telescope ‘giant man-bats’ on the moon. This sensation was published in the New York Sun as a series of stories about these goat-like, blue creatures. It was, of course, completely made up by the editor because no one could prove it—the stories pushed circulation from 8,000 to 19,000 copies.

Today, many things are called fake news that aren’t fake. Dietmar stresses there is a difference between fake news and propaganda, which he defines as ‘the organized dissemination of information to assist or damage the cause of a government’. We know from history that propaganda has caused the world much pain—through World War II, and the red scare in the U.S.

In the past, media accused governments of lying and creating stories, but this has been turned on it’s head during the Clinton/Trump election—with the invention of ‘alternative facts’.

Dietmar gives a few examples for us to show how the media industry is in trouble. In the past, many resources were needed to create a campaign. You needed media power, staff, distribution. This is not necessarily true anymore due to social media:

Social media’s reach is massive. Anyone, anywhere, could start a rumour and it could spread. Additionally, a large part of the population gets their news from social media. This is more and more worrying when you take a look at the top trending stories on social media: such as Obama wanting to ban the Pledge of Allegiance, and the Pope advocating for Trump.

Dietmar also mentions fake accounts that disseminate these types of stories—such Russian-backed advertisements on Facebook, and fake Twitter accounts advocating topics the real individual wouldn’t agree with.

We are given a definition of mass media: ‘the means of communication that reaches large number so for people in a short time, such a television, newspapers, magazines, and radio. Perhaps not so up to date anymore. Dietmar discusses newspaper readership—newspapers are no longer mass media, they are niche. Additionally, trust in media has plunged to an all-time low.

Dietmar makes a note: we, as media, cannot blame anyone but ourselves for this fall in trust. He uses an example of a story that was run on Express, which was then taken on by Independent, The Telegraph, and The Daily Mail. The story was about a pastor that was eaten by a crocodile, while demonstrating Jesus’ ability to walk on water. Independent, The Telegraph, and The Daily Mail ran this story without realizing it was initially published by a satire website. The story was completely untrue.

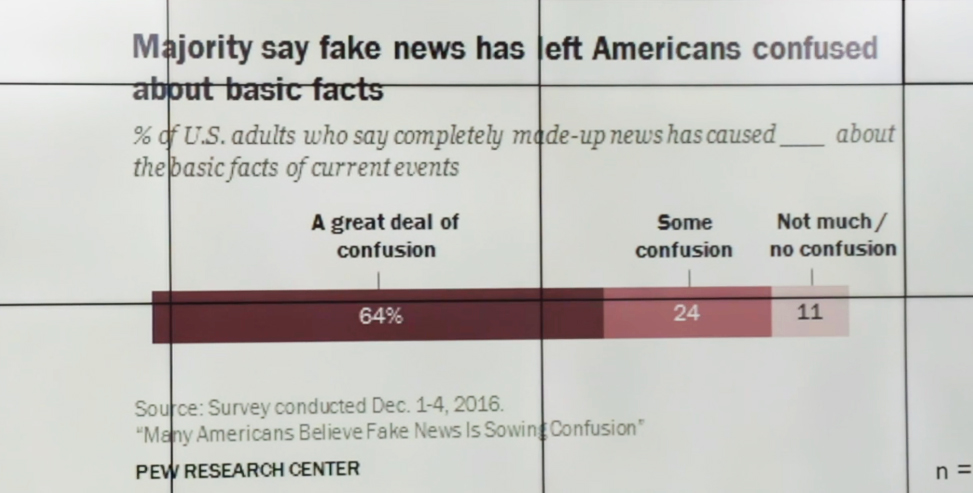

Dietmar shares some stats:

Americans are confused by the media. We as media, as an industry, are confusing our readers. Journalists are not doing enough research to produce ‘good’ content, and readers aren’t doing enough research to know the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

Why is this? Media is everywhere. Dietmar shares some stats, that the average person is exposed to media about 12 hours a day. We simply don’t’ have enough time to analyse and research what is accurate information.

Dietmar then delves into the dangers of sponsored content. Native advertising doesn’t help to build trust. The audience is essentially tricked into believeing that sponsored content is the same as stories written by an editorial—there is not enough done to distinguish between the two of them. He shares the statistic that 80% of young people believe a native ad is a real news story.

So what can we do? Diemtar talks about websites such as Le Decodeurs (of France) and Reality Check (BBC) that verify if a story or image is true.

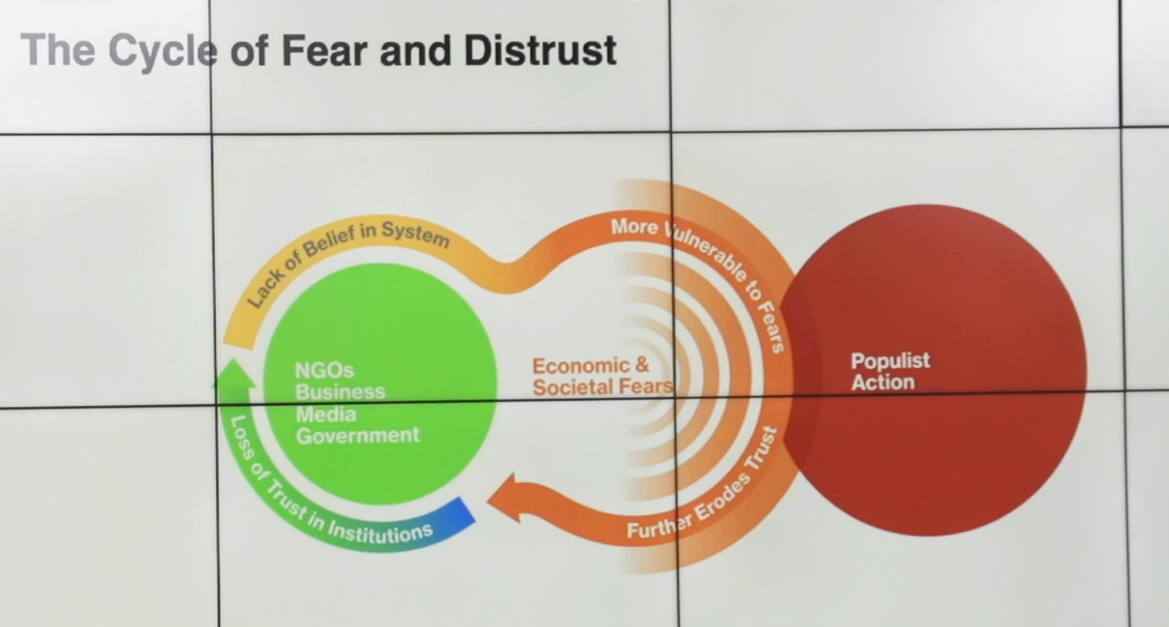

He further emonstrates the danger of fake news by talking the audience through the cycle of fear and distrust:

The only chance media companies have today is to build up trust again—and we can do this by using good journalistic practices, and putting together accurate content.